Deccan Traps panorama looking east from Kate’s Point, Mahabaleshwar. The peaks rise ~1400 meters above sea level and ~600 meters above the Krishna river valley.

Geological Period

Upper Cretaceous to Paleocene

Main geological interest

Volcanology

Igneous and Metamorphic petrology

Location

Southern Asia, India

17°55’16”N, 073°40’30”E

Deccan Traps panorama looking east from Kate’s Point, Mahabaleshwar. The peaks rise ~1400 meters above sea level and ~600 meters above the Krishna river valley.

The best-studied section and tourist hotspot in the Deccan Traps, one of the world's great continental flood basalt provinces.

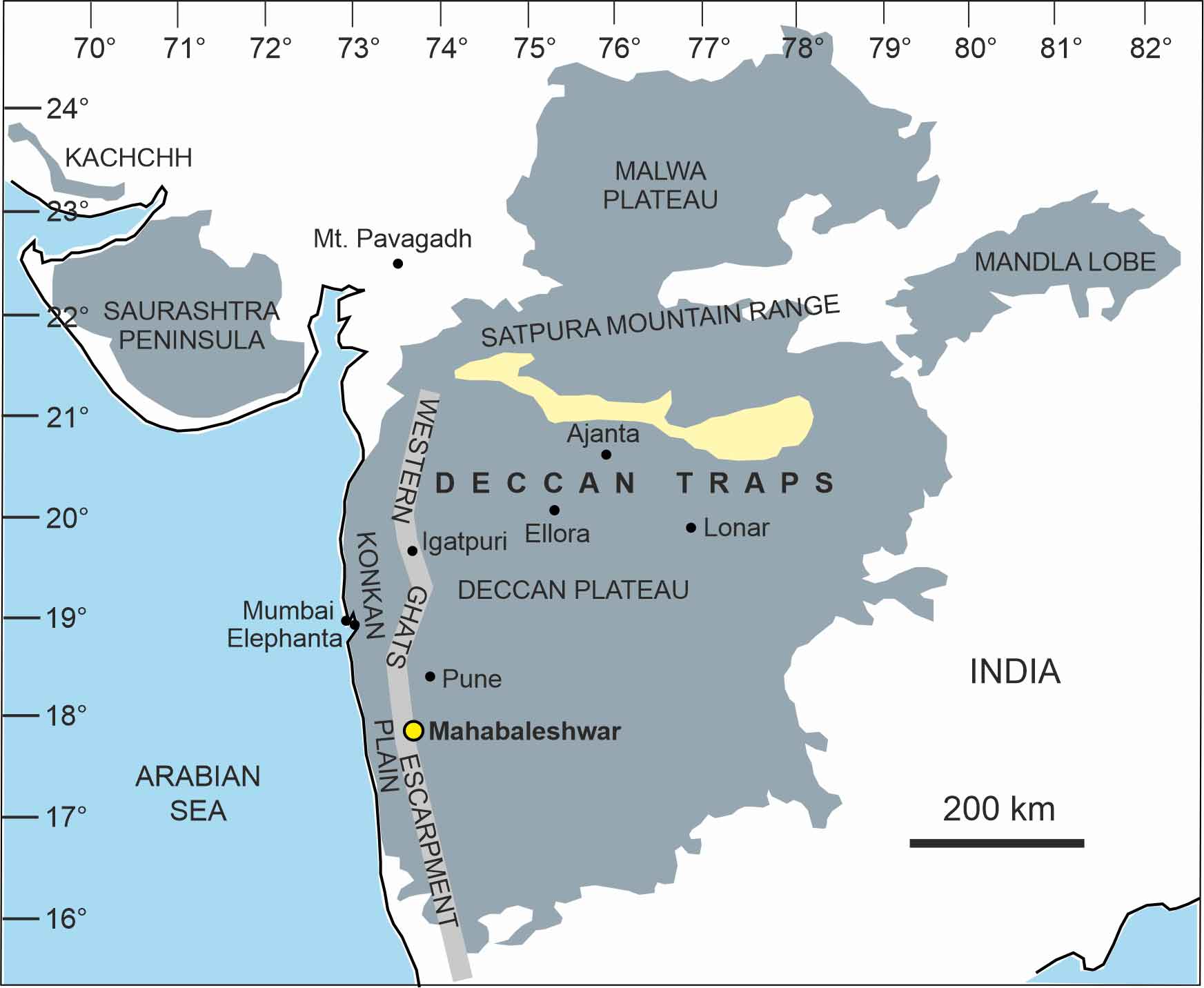

The Deccan Traps is of great importance in volcanology, igneous petrology, geochemistry, geochronology, planetary geology, geophysics, geodynamics, palaeontology, and flood basalt-hosted groundwater and petroleum reservoirs and carbon dioxide sequestration. It is also important for Palaeogene-age ferricrete duricrusts formed by basalt weathering (Ollier and Sheth, 2008), hundreds of rock-cut caves (including UNESCO World Heritage sites) depicting human history and culture (Sheth, 2023), heritage stones (Kaur et al., 2019), spectacular secondary minerals (Ottens, 2003), and Lonar, Earth’s only known hypervelocity impact crater in basalt (Bodas and Sen, 2014). Mahabaleshwar, the best-studied Deccan section, is already prominent on the tourism map of India.

- Geological description

The Late Cretaceous to Palaeocene (~65 Ma) Deccan Traps continental flood basalt province contains hundreds of tholeiitic basalt lava flows. Each flow represents a dyke-fed fissure eruption similar to, but vastly larger than, modern Hawaiian and Icelandic eruptions. With individual 1000 km3 eruptions releasing 10 gigatons of carbon dioxide and sulphur dioxide each to the atmosphere, Deccan volcanism played a critical role in the Cretaceous/Palaeocene (K/Pg) boundary mass extinction. The province still covers 500,000 km2 in west-central India, excluding substantial parts downfaulted into the Arabian Sea during India-Seychelles rifting at 62.5 Ma, or eroded away. The still-preserved basalt thickness (including subsurface thickness) in the Western Ghats escarpment, beside the rifted margin, is ~2 kilometers. Mahabaleshwar town (1436 meters above mean sea level) in the Western Ghats sits atop an ~1200 meter-thick sequence of about 50 lava flows, capped by a thick, regional ferricrete duricrust formed by Palaeogene weathering. The Mahabaleshwar section is the most intensely studied stratigraphic section in the province for petrology, geochemical stratigraphy, geochronology and palaeomagnetism. Mahabaleshwar, with its pleasant climate, great scenic beauty and easy access, also attracts hundreds of thousands of tourists every year, and thus has very high geoheritage and geotourism value (Sheth, 2014).

- Scientific research and tradition

Deccan Traps research dates back at least two centuries (~1830’s), with most of the early works by geologists of the Geological Survey of India, many of them British. Modern Deccan research is vigorous and truly international, with many active groups particularly from India, France, Italy, Japan, Russia, UK, and USA.

- Reference

Bodas, M.S. and Sen, B. (2014) ‘The Lonar Crater: The Best Preserved Impact Crater in the Basaltic Terrain’, in V.S. Kale (ed.) Landscapes and Landforms of India. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands (World Geomorphological Landscapes), pp. 223–230. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8029-2_24.

Kaur, G. et al. (2019) ‘The Late Cretaceous-Paleogene Deccan Traps: a Potential Global Heritage Stone Province from India’, Geoheritage, 11(3), pp. 973–989. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-018-00342-1.

Ollier, C.D. and Sheth, H.C. (2008) ‘The High Deccan duricrusts of India and their significance for the “laterite” issue’, Journal of Earth System Science, 117(5), pp. 537–551. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12040-008-0051-9.

Ottens, B. (2003) ‘Minerals of the Deccan Traps, India’, Indian zeolites and related species, The Mineralogical Record, 34(1), pp. 5–83.

Sheth, H. (2023) ‘The Volcanic Geoheritage of the Ajanta and Ellora Caves, Central Deccan Traps, India’, Geoheritage, 15(1), p. 39. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-023-00809-w.

Sheth, H.C. (2014) ‘Mahabaleshwar, Deccan Traps, India’, International Journal of Earth Sciences, 103(3), pp. 799–799. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-013-0943-z.

- Author(s)

Hetu Sheth.

Indian Institute of Technology Bombay.

Satish C. Tripathi.

The Society of Earth Scientists, Lucknow, India.