1940s aerial view of the Esmark’s moraine a few years before the moraine was covered by a pine forest, and the sandur plain, in the foreground. (Widerøe/Hestmark/Djuv).

Geological Period

Pleistocene to Holocene

Main geological interest

History of geosciences

Geomorphology and active geological processes

Location

Rogaland and Innlandet counties, Norway

Otto Tank:

61°53’37”N, 007°26’18”E

Esmark:

58°54’14” N, 008°08’14”E

1940s aerial view of the Esmark’s moraine a few years before the moraine was covered by a pine forest, and the sandur plain, in the foreground. (Widerøe/Hestmark/Djuv).

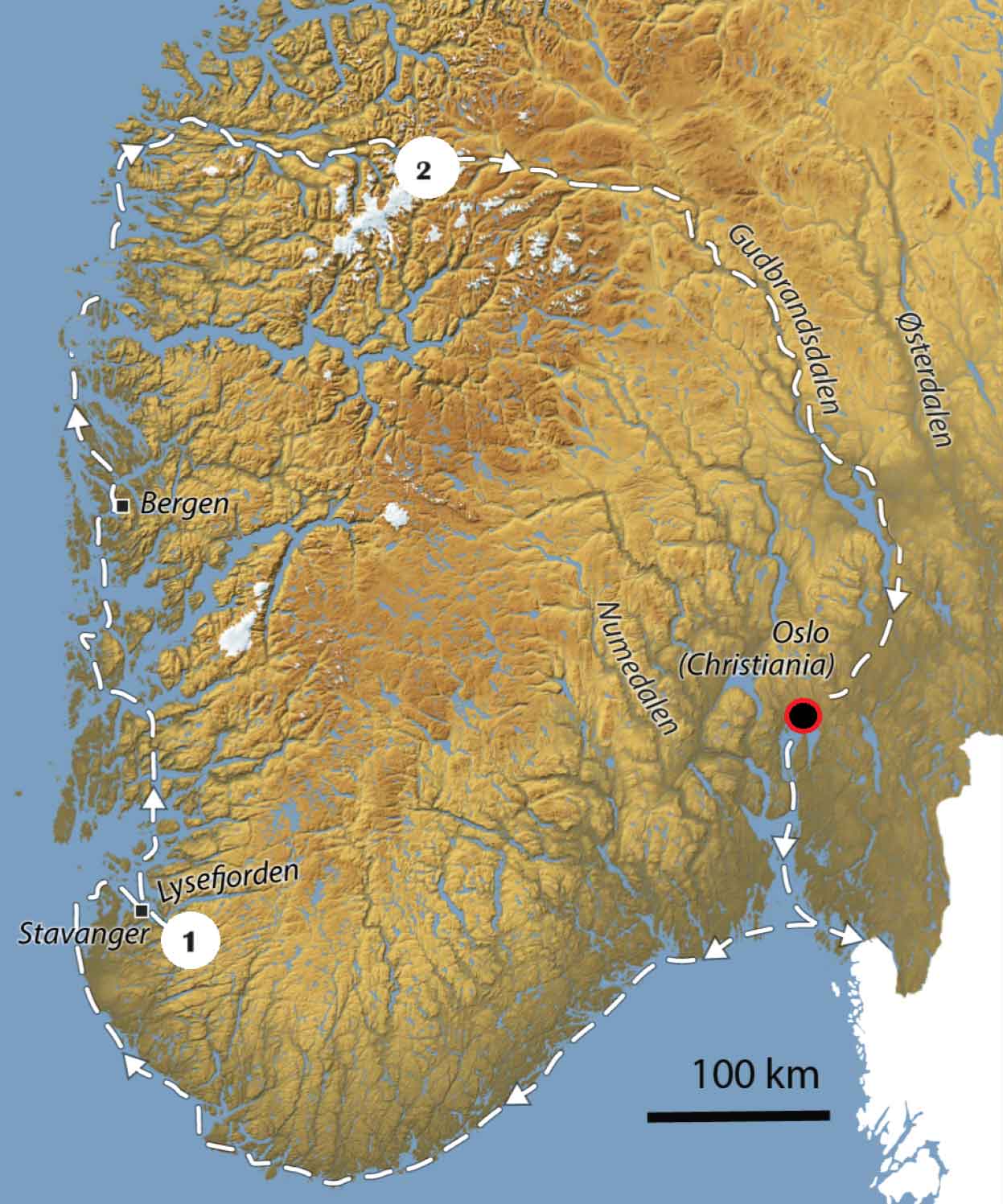

The sites where Jens Esmark discovered the Ice Age in 1823.

The comparison of these two moraines, one deposited at the end of the last ice age at sea level where no glaciers are present today and one recently deposited by an extant glacier in the high mountains, made Jens Esmark and his accompanying student Otto Tank, during their fieldwork in 1823, realize that Norway and Northern Europe had formerly been covered by big glaciers reaching all the way down to sea level, glaciers that had carved out valleys and fjords. The close observation of an extant glacier and its landscape effects thus proved crucial to the discovery of ice ages.

- Geological description

The geomorphological phenomena created by glaciers -moraines, erratic boulders and polished and striated rock surfaces- are the telltale signs of the former presence and greater extension of glaciers in areas where they are today absent. They thus also signal a past colder climate when ice covered a greater part of Earth’s surface.

The two moraines are situated transversally in two valleys and mainly differ in size. The Esmark Moraine, deposited at the end of the last ice age close to sea level, is about five times bigger than the Otto Tank Moraine. They both contain a mixture of rock sizes from boulder to clay – a diamicton. Otto Tank’s Moraine was deposited by the northern tip of Europes biggest extant glacier Jostedalsbreen at the culmination of the so-called ‘Little Ice Age’ around 1750 AD at 1040 m. above sea level in what is today Breheimen national park. In front of both moraines are typical sandur plains where braided glacial rivers once or still flow, depositing the fine bedrock material crushed by the advancing glacier.

- Scientific research and tradition

The Esmark moraine was well described by Esmark (1824, 1826) and was been studied by others, e.g. Worsley, 2006. The Otto Tank Moraine was ‘rediscovered’ by Hestmark in 2008 and published in Hestmark (2017, 2018).

- Reference

Esmark, J. (1824) ‘Bidrag til vor Jordklodes Historie’, Magazin for Naturvidenskaberne (Anden Aargangs förste Bind, Förste Hefte), 3, pp. 28–49.

Esmark, J. (1826) ‘Remarks tending to explain the Geological History of the Earth’, The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, 2 [First part October-December 1826], pp. 107–121.

Hestmark, G. (2017) Istidens Oppdager. Jens Esmark, pioneren i Norges fjellverden. Oslo: Kagge Forlag.

Hestmark, G. (2018) ‘Jens Esmark’s mountain glacier traverse 1823 − the key to his discovery of Ice Ages’, Boreas, 47(1), pp. 1–10. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/bor.12260.

Krüger, T. (2013) Discovering the Ice Ages: International Reception and Consequences for a Historical Understanding of Climate. Leiden, Brill. Available at: https://brill.com/display/title/22701.

Worsley, P. (2006) ‘Jens Esmark, Vassryggen and early glacial theory in Britain’, Mercian Geologist, 16, pp. 161–172.

- Author(s)

Geir Hestmark.

CEES, Department of Biosciences, University of Oslo and INHIGEO. Norway.