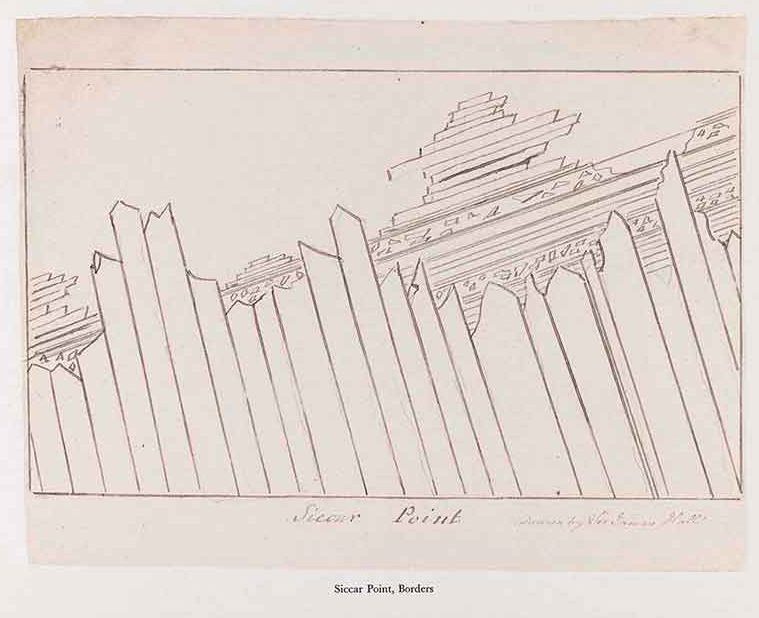

Hutton’s Unconformity at Siccar Point with a geotourist for scale. The figure is standing on shallowly dipping Devonian rocks that rest unconformably upon steeply dipping Silurian-aged rocks beneath (Photo: Colin MacFadyen/NatureScot).

Geological Period

Lower Silurian – Upper Devonian

Main geological interest

History of geosciences

Stratigraphy and sedimentology

Location

Cockburnspath, Berwickshire, Scottish Borders, Scotland, UK.

55°59’15.0″N, 2°24’24.0″W

Hutton’s Unconformity at Siccar Point with a geotourist for scale. The figure is standing on shallowly dipping Devonian rocks that rest unconformably upon steeply dipping Silurian-aged rocks beneath (Photo: Colin MacFadyen/NatureScot).

An iconic and important site where James Hutton recognized the significance of unconformities and the possibility for “deep time” in geoscience.

James Hutton (1726–1797) envisaged in his Theory of the Earth (1795) not only processes that weather and destroy rocks, and thus ruin a perfectly created world, but also processes capable of regenerating the Earth. This led Hutton to propose the existence of continual, cyclical Earth processes which could drive change over long timescales. The spectacle of the unconformable relationship between the two different rock sequences at Siccar Point provided Hutton the empirical evidence for previous cycles of his Earth machine. Hutton used the location to demonstrate the existence of cycles of deposition, folding, and further deposition of rocks that which the unconformity represents. He understood the implication of unconformities in the evidence they provided for the enormity of geological time and the antiquity of the Earth.

- Geological description

Siccar Point is a coastal promontory that beautifully displays in three dimensions the spectacular angular unconformity with Upper Devonian beds resting discordantly on folded, near vertical, Lower Palaeozoic strata. The Lower Palaeozoic beds are turbiditic dark grey, fine grained wacke sandstone and interbedded finely laminated, fissile mudstone of the Gala Group, of early Silurian (Llandovery Epoch) age (Browne and Barclay, 2005). These rocks were strongly deformed, being folded and cleaved, during the Caledonian Orogeny. Subsequent erosion, pre-Late Devonian times, formed an irregular surface with considerable palaeorelief through differential rates of weathering and erosion of individual beds in the Silurian succession; beds of wacke sandstone standing up more sharply and prominently than others (Greig, 1988; Treagus, 1992). Upon the sharp angular unconformity there rests Upper Devonian strata, comprising reddish brown breccia and conglomerate, of the Redheugh Mudstone Formation of the Stratheden Group. In marked contrast to the underlying Silurian strata the Upper Devonian beds have only a gentle inclination produced during the later, here less intense, Variscan Orogeny.

The unconformity played a key role in James Hutton’s insight that geological processes are not just “destructive” but also capable of restoring thus leading to a rock cycle of indefinite duration so “that we find no vestige of a beginning, – no prospect of an end” (Hutton, 1788: 304).

- Scientific research and tradition

Siccar Point is of great historical importance in the development of geoscience as evidence supporting James Hutton’s celebrated Theory of the Earth that in its final form proposed a cycle of geological processes (Dean, 1992). The locality also became the celebrated nexus for empirical argument concerning the great age of the Earth.

- Reference

Browne, M.A.E. and Barclay, W.J. (2005) ‘Siccar Point to Hawk’s Heugh, Scottish Borders’, in The Old Red Sandstone of Great Britain. Barclay, W.J., Browne, M.A.E., McMillan, A.A., Pickett, E.A., Stone, P. and Wilby P.R. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee (Geological Conservation Review Series, 31), pp. 181–187.

Dean, D. (1992) James Hutton and the History of Geology. Cornell University Press: Ithaca.

Greig, D.C. (1988) Geology of the Eyemouth District. Sheet 34 (Scotland). London: HMSO, p. 78.

Hutton, J. (1788) ‘Theory of the Earth; or an investigation of the laws observable in the composition, dissolution, and restoration of land upon the Globe’, in Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburg. (1), pp. 209–304.

Hutton, J. (1795) Theory of the Earth. With Proofs and Illustrations (I and II). Cadell & Davies, London; William Creech, Edimburg.

Treagus, J.E. (1992) ‘Siccar Point’, in Caledonian Structures in Britain South of the Midland Valley. Treagus, J.E. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee (Geological Conservation Review Series, 27), pp. 17–19.

- Author(s)

Colin MacFadyen

NatureScot, Scotland’s Nature Agency, Scotland, U.K

Martina Kölbl-Ebert

International Commission on the History of Geological Sciences (INHIGEO) & Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences University of Munich, Germany

Helen Fallas

British Geological Survey, Edinburgh, U.K.