Fault and joint controlled linear alignments among cockpits, near to the Alps, along the north eastern boundary of the Cockpit Country (photograph: Mr. Jack Tyndale-Briscoe).

Geological Period

Miocene to Holocene

Main geological interest

Geomorphology and active geological processes

Stratigraphy and sedimentology

Location

West Central, Jamaica

18°18’36”N, 077°37’48”W

Fault and joint controlled linear alignments among cockpits, near to the Alps, along the north eastern boundary of the Cockpit Country (photograph: Mr. Jack Tyndale-Briscoe).

One of the most outstanding areas of limestone Cockpit karst in the World, located in the Caribbean.

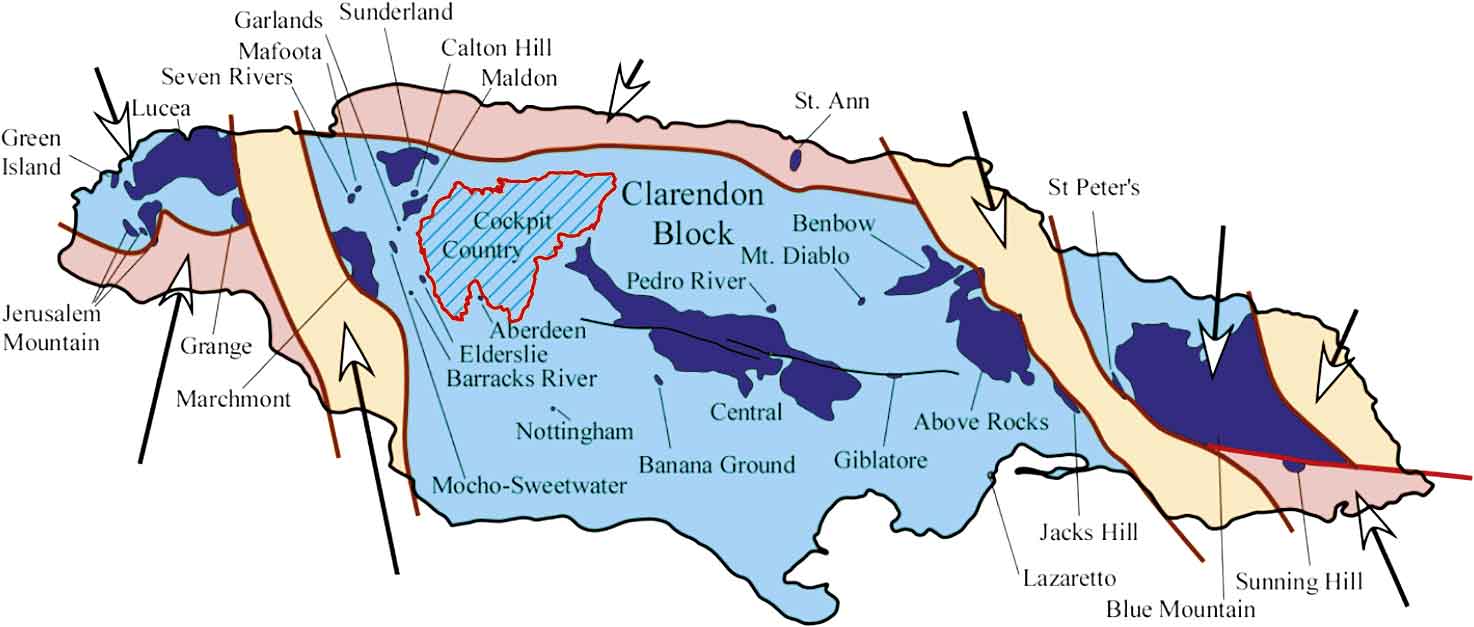

The type area for Cockpit Karst developed on uplifted limestone in a tropical region. The area represents one of the World’s most important and spectacular geomorphological landscapes of 1300 km2, 12% of the entire area of Jamaica. Geology and the microclimate generated high endemism and biodiversity. The area is underlain by a network of underground streams and caves. The inhospitable environment served as refuge for freed Spanish enslaved Africans in 1655 and later served as refuge for runaway enslaved Africans, whose descendants still reside in the area.

- Geological description

A thick sequence of platform limestones and dolostones was deposited in the late Eocene to early Miocene with combined thicknesses of 1,000 to 1,500 meters. A layer of early- to mid-Miocene ash from volcanos in Central America accumulated on the limestone plateau during its early emergence and underwent extensive leaching to form bauxitic soils. Uplift from the late Miocene to present has seen extensive karst formation characterized by the production of conical residual hills up to 100 meters high separated by star-shaped to linear depressions hosting bauxite deposits. Two mechanisms of karst formation are generally recognized. The first is due to solution following rainfall. The second is by collapse. The distinct land forms include conical residual hills (cockpit karst), steep-sided hills of limestone and dolostone (tower karst), isolated to star-shaped depressions (dolines or sinkholes), and larger more complex depressions with multiple dolines (uvalas). The resulting landscape lacks surface drainage. Despite the lack of surface drainage there is a tremendous network of underground streams that form part of an intricate caving system. The area is internationally recognized for its karst scenery and its tropical wet-limestone forests, which give rise to its high endemism and biodiversity.

- Scientific research and tradition

Cockpit Country and its karst were described by Sawkins (1969) during the first government geological survey. Subsequently the limestones have been described by Mitchell (2013) and the karst by Sweeting (1958), Mitchell et al. (2003) and Miller (2004). Cockpit Country has been designated a protected area by the Government.

- Reference

Dwyer, S. and Smickle, D. (2004) Cockpit Country hydrological assessment: A Desk Study of the Hydrological and Hydrogeological Regime Governing Flow in the Cockpit Country of Jamaica. Water Resources Authority & The Nature Conservancy.

Miller, D.J. (2003) ‘Karst geomorphology of the White Limestone Group’, Cainozoic research, 3(1/2), pp. 189–219.

Mitchell, S., Miller, D.J. and Maharaj, R. (2003) ‘Field guide to the geology and geomorphology of the Tertiary limestones of the Central Inlier and Cockpit Country’, Caribbean Journal of Earth Science, 37, pp. 39–48.

Mitchell, S.F. (2013) ‘Stratigraphy of the White Limestone of Jamaica’, Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, 184(1–2), pp. 111–118. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2113/gssgfbull.184.1-2.111.

Sawkins, J.G. (1869) Reports on the Geology of Jamaica; Or, Part II. of the West Indian Survey. Printed for H.M . Stationery Off ., Longmans, Green, and Co. (Memoirs of the Geological Survey). Available at: http://archive.org/details/reportsongeolog00hoffgoog.

Sweeting, M.M. (1958) ‘The Karstlands of Jamaica’, The Geographical Journal, 124(2), pp. 184–199. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/1790245.

- Author(s)

Simon F. Mitchell.

University of the West Indies, Mona, Kingston. Jamaica.

Sherene James-Williamson.

University of the West Indies, Mona, Kingston. Jamaica.

David Miller.

University of the West Indies. Jamaica.