Upper Jurassic Carnegie Quarry Dinosaur Bone Site

United States of America

Articulated skull and cervical vertebrae of Camarasaurus as seen on the quarry face.

Geological Period

Upper Jurassic

Main geological interest

Paleontology

Stratigraphy and sedimentology

Location

Northeastern Utah, United States of America

40°26’26”N, 109°18’04”W

Articulated skull and cervical vertebrae of Camarasaurus as seen on the quarry face.

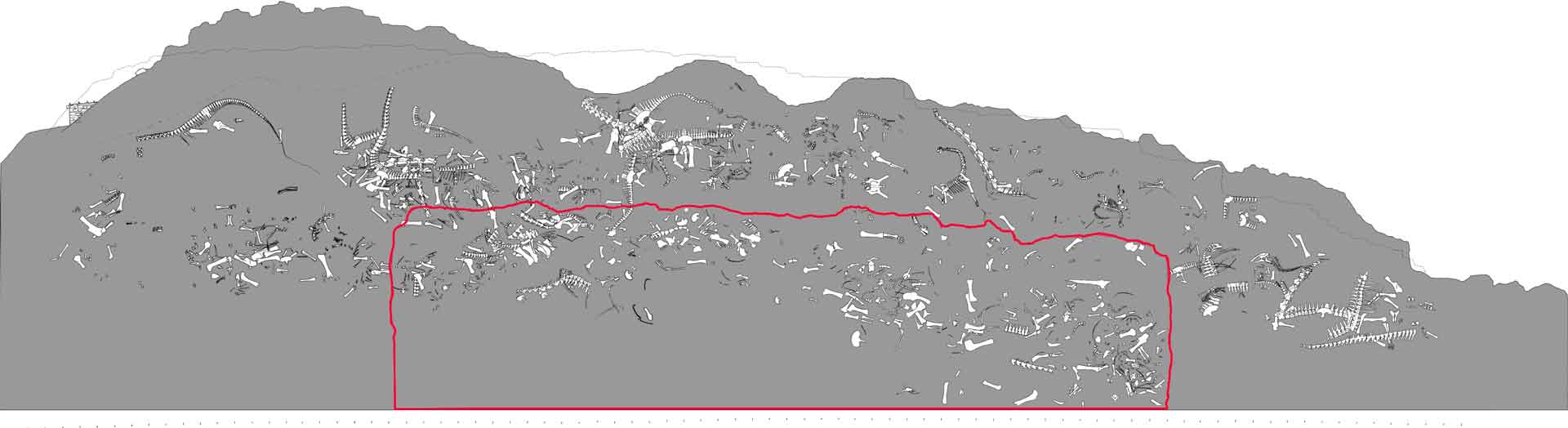

Showcasing an in-situ wall of over 1500 bones representing nine Late Jurassic dinosaur species.

The Quarry stands as a prime example of a geoconservation site, housing authentic dinosaur bones preserved in rock and protected by a steel, concrete, and glass structure. Discovered in 1909 by Carnegie Museum crews, the site quickly became a geotourist attraction. The on-site exhibition showcases dinosaur bones in their original setting, mirroring their deposition some 150 million years ago in an ancient riverbed. Complementary exhibits explore the Late Jurassic paleoenvironment of the region, spotlighting fossils excavated from both the Quarry and its environs.

- Geological description

The Carnegie Quarry Exhibit Hall, situated in Dinosaur National Monument, spans 585 square meters of steeply inclined fluvial sandstone. Within, 1500 in-situ dinosaur bones from nine dinosaur species and freshwater bivalves offer insights into the biodiversity and an ecosystem in the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. A recent Pb/U date of 150.77 Ma places the bone deposit near the top of the Kimmeridgian.

Sedimentological and taphonomic analyses attribute the three bone layers to drought periods, when decaying carcasses accumulated in a braided river system. Various bone configurations, from complete skeletons to scattered parts, reveal fluvial transport. Significantly, many bones display evidence of upstream scour, indicating a novel finding that bones within dynamic depositional settings facilitated their own burial.

The deposit showcases diverse Late Jurassic dinosaur species, including sauropods, theropods, stegosaurs, and ornithopods and has long been used as representing Late Jurassic dinosaurs to the public. Furthermore, the Quarry produced the Apatosaurus louisae type specimen, unveiling the first evidence of a whip-like tail in sauropods. Size variation in Camarasaurus provides insights into growth changes. Dinosaurs from the quarry are displayed in various North American museums, some as the sole skeletons of their species, highlight the Quarry’s paleontological significance.

- Scientific research and tradition

Discovered in 1909, the dinosaur fossils from the quarry have played an important role in defining Late Jurassic dinosaur taxonomy and paleoecology in North America. More recent studies have focused on the depositional and taphonomic settings (Bilbey et al., 1974; Lawton, 1977; Carpenter, 2013, 2020, 2023) and site history (Carpenter, 2018).

- Reference

Bilbey, S.A., Kerns, R.L. and Bowman, J.T. (1974) Petrology of the Morrison Formation, Dinosaur Quarry Quadrangle, Utah. Salt Lake City: Utah Geological and Mineral Survey, Utah Dept. of Natural Resources (Utah Geological and Mineral Survey Special Studies, 48).

Carpenter, K. (2013) ‘History, Sedimentology, and Taphonomy of the Carnegie Quarry, Dinosaur National Monument, Utah’, Annals of Carnegie Museum, 81(3), pp. 153–232. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2992/007.081.0301.

Carpenter, K. (2018) ‘Rocky Start of Dinosaur National Monument (USA), The World’s First Dinosaur Geoconservation Site’, Geoconservation Research, 1(1), pp. 1–20. Available at: https://doi.org/10.30486/gcr.2018.539322.

Carpenter, K. (2020) ‘Hydraulic modeling and computational fluid dynamics of bone burial in a sandy river channel’, Geology of the Intermountain West, 7, pp. 97–120. Available at: https://doi.org/10.31711/giw.v7.pp97-120.

Carpenter, K. (2023) ‘Reconstructing the floodplain paleogeography associated with the Quarry River, Dinosaur National Monument, Utah, USA’, in J.I. Kirkland, R. Hunt-Foster, and M. Loewen (eds) The Anatomical Record. 14th Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biota., Salt Lake City, Utah: Utah Department of Natural Resources, pp. 65–67.

Lawton, R. (1977) ‘Taphonomy of the dinosaur quarry, Dinosaur National Monument’, Rocky Mountain Geology, 15(2), pp. 119–126.

- Author(s)

Kenneth Carpenter.

University of Colorado Museum, Boulder, Colorado USA.

John Foster.

Utah Field House of Natural History State Park Museum, Vernal, Utah USA.

ReBecca Hunt-Foster.

National Park Service, Dinosaur National Monument, Jensen, Utah USA.